In an interesting article, How Our Brains Go the Distance, Virginia Hughes tells us:

People think about distances all day… long. Distance can describe physical spaces (a far-flung city; a nearby store), time (distant past; near future), and social relationships (near-and-dear pals; a quarreling couple needing some space).

Researchers have long thought that these various examples of “psychological distance” are represented by some of the same circuits in the brain. A new brain-imaging study strongly bolsters the idea, finding that certain patterns of neural activity underlie all of our judgments about distance — whether in space, time, or the social realm.

The results makes sense, the researchers say, given that all of these distances have something in common: They give us a way to move beyond the visceral, here-and-now experience of our lives. More provocatively, this ability to “go the distance” might be uniquely human.

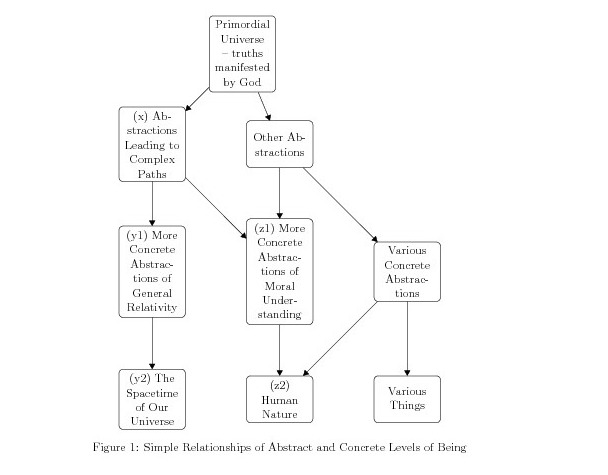

This is probably necessary to the `higher-level’ claims I’ve made that human beings can abstract from concrete or relatively concrete levels of created being to relatively abstract levels of created being. I’ve particularly emphasized geometric reasoning in my claim we can gain some sort of a better handle on our moral messes by using qualitative reasoning borrowed from modern physics and mathematics, borrowed perhaps by an abstraction of that reasoning from, say, the analysis of spacetime in our universe, followed by a movement toward the concrete levels of human morality, or of human life in general.

I’ll reuse a diagram from several years ago, one I recently reused in How a Christian Finds Metaphysical Truths in Empirical Reality:  .

.

I originally published that diagram in The Liberal Mind: The Essence of Liberalism where I claimed:

What we need, in terms set by this essay, are thinkers who can move up to higher levels of abstraction to figure out how our human natures and communities become more complex and richer in possibilities (even the most passive of individual human beings have natures which are more complex just because of our more complex communities). I’m suggesting that we can learn many tricks from modern physicists and mathematicians and might very well be able to borrow directly from what has been learned from the exploration of spacetime, matter and energy and fields, and even the most abstract regions of mathematics.

The article, How Our Brains Go the Distance, also tells us:

What most surprised me about this research is its possible connection to empathy and “theory of mind,” or the ability to take the mental perspective of someone else. About a decade ago, researchers linked theory of mind to a specific region in the brain: the temporo-parietal junction (TPJ). Intriguingly, the TPJ region encompasses the IPL.

Theory of mind may be another way that we have evolved to look beyond our immediate, individual perspective, notes Nira Liberman, a social psychologist at Tel Aviv University. “We predict the behavior of other people by forming abstract mental constructs,” she says. “All these different ways of traversing immediate experience were and are achieved by abstract mental representations.”

See Rebecca Saxe: Fine tuning the theory of mind for the discussion about “theory of mind”.

I also discussed this issue of empathy in prior essays: Through the Body Comes Sin, Through the Body Salvation: Part 1 back in March of 2008 and The Embodied But Constructed Self. In that second essay, I wrote:

It’s odd to those who feel a need to think of a human being, their own self or another, as having some sort of well-formed existence given at conception or maturity or whatever. This is the mistake of thinking of an empirical creature, a human being, as metaphysically grounded, a complete being thought of as perhaps a `person’. I might describe this as `backdoor’ Platonism, a replacement of an ultimately erroneous but plausible and rationally stated understanding of being by mere assumptions, prejudices of a sort guaranteed to decay into superstitions if held too firmly and too consistently.

We are embodied but our individual `selves’ are constructed by our interactions with our own bodies and with a lot of surrounding entities, some of them abstract and not embodied, at least not in a direct way. (Embodiment can be a misleading description of, say, a community but it is a valid description if properly qualified by references, for example, to past and future generations or even the me of last year and the you of ten years from now.)

We are, in some reductionistic but legitimate sense, mappings in our brains, mappings which include both our individual and communal selves.

That last line is important. Our individual selves are created by processes in this mortal realm, processes which produce imperfect and incomplete results in a world which allows no better. After all, if the process could be completed in this world, God’s story would end at that point. More importantly for my current purposes, our communal selves are constructed by mappings in our brains. Mappings similar to those which shape our human animal beings as individuals of a truer sort shape our human tribes and clans as communities of a truer sort—though I believe we become `persons’ in a greater sense only when we also become a part of the perfect and complete community: the Body of Christ.