One of my favorite, perhaps overused, quotations is from the historian Carroll Quigley:

The truth unfolds in time through a communal process.

In this idea, we have a better definition of a true Christian traditionalism or conservatism. Does it serve to define other forms of traditionalism and conservatism? Put that question aside for a short while. I’ll provide my own understanding of what it is that we Christians are to learn from tradition and from the current state of the world, my own understanding of what it is that we are to conserve.

A Christian conservative, unlike perhaps most others, isn’t interested — at least, shouldn’t be interested — in preserving a particular social or economic or political structure in this passing and mortal world. In general, the Bible itself presents no such structures, nor even an ecclesiastical structure, which we modern Christians would think to be worth reviving or conserving. Jesus Himself denied the absolute value of the family and of the Sabbath.

If the Christian Bible is unsettling in denying the primacy of much that conservatives would declare among the Permanent Things, what does it give us? It gives us a variety of books of prophecy, wisdom writings, histories of ancient Semites, four strangely limited biographies of Jesus of Nazareth, and various sorts of writings of followers of that same Jesus. Overall, the Christian Bible gives us a story, a narrative directed to the moral purposes of the Creator. And it gives us stories of attempts to respond to God’s world, some attempts being successes and others being failures and others having ambiguous results. It doesn’t tell us where the story is heading nor does it tell us exactly how to play our parts in that story, but it does give us much in the way of advice on how to find our way in that story.

A Christian traditionalist or conservative, as paradoxical as this might first seem, is concerned with the forward movement of God’s story and only concerned about the things of tradition to the extent they are are playing a valid part of this ongoing story or are helping us to understand this story in which they no longer play a part. We aren’t called to preserve the structures or ways of David’s kingdom nor the ways of simple Hebrews at the time of Jesus nor those of on-the-move evangelists over the next century or so. Why would we think our calling is to preserve the ways, political or social or economic or cultural, of Italy during the Middle Ages or England during the Age of Reason or Germany during the glory years of the ruthlessly rational and remarkably competent Bismarck or Europe during the exciting decades before the guns let loose in August of 1914 or even working-class Waukegan during the boyhood of the recently deceased Ray Bradbury? We certainly aren’t called upon to conserve the American way of life in its current morally disordered state.

In this world, we are characters in God’s story, participants in the Body of Christ as that Body develops in its mortal form as a community of mortal creatures. It’s the story, the Body in its entirety, not the organs of that Body which are important; those organs might come and go during mortal development. It’s the story, not the structures in which those organs are set, structures not necessarily less mortal than many of the organs. As the kingdoms of Israel and Judah came and went, so will the United States. As the Aristotelian summation of all that was worth knowing came and went, so will modern forms of knowledge, including the forms I’m developing. Certainly the Christian Church will persevere for She is the organ of worship and of moral and spiritual order, but She will change. She has to change for She is currently so ineffective at even properly shaping Her priests and bishops and other ministers, so cowardly in the face of criminal wars and abuses by the powerful, so falsely charitable when accepting checks to do works from centralized welfare-warfare powers, so falsely courageous when the battle is lost or when those powers threaten something of direct interest to the bishops.

The story continues. To uphold tradition properly, we must study and explore in God’s Creation. We must learn to see even slight hints of His acts of creation, His acts of shaping what He has created, and to see the slighter hints of His purposes which might tell us where the story is headed. What is the Good Lord up to? We now know the Creator’s story is set in a spacetime which seems strange to us. We know also that matter and movement and relationships between entities aren’t what we would think from our ordinary lives. We have learned, by shedding of much blood and destruction of much important infrastructure and art, that human nature — especially when united in certain types of political movements — is capable of great evil: masses of nice men can reluctantly but faithfully serve a Hitler or Stalin rather than join the persecuted.

The good we have learned to do in living our parts in this story can have a dark side — the technology which has raised living standards and increased expected life-spans can destroy human relationships and can also destroy or badly damage some parts of our physical environments and can also stimulate selection processes on infectious organisms which might produce truly horrible epidemics.

The bad we have learned to do can at least hint at the side of light and goodness — some sadistic barbarians, such as the Assyrian emperors or William the Conqueror, have formed political entities which proved to be good settings for the development of better forms of organization such as countries republican in government and capitalist in economy. Should we celebrate that some of the good in our modern world came from the sufferings of those raped and murdered, enslaved or left with no way of making a living, by one conqueror or sometimes a parade of such brutes? No, but, as I implied in the paragraph above, we should be careful in celebrating even the good we do — it might not be so fully good as we think. We should be joyful for the gifts of God and should ponder how to properly use those gifts and should wonder at the complex nature of those gifts which so often bite us and bite hard.

Even when those inclined to morally well-ordered motivations fall into evil, the ensuing repentance can lead to deeper understandings of moral and spiritual order and to a proper sort of liberalism, generosity of spirit and openness of mind. Such periods can also lead to that old problem of tossing the baby out with the bathwater, beliefs are shed along with the desire to torture or kill those who disagree with us. During the 1950s and 1960s, Europe showed some promise of having truly renounced her efforts to commit continental suicide. Then, prosperity brought back the hubristic traditions and Europeans have seemingly discovered a way both old and new to destroy their continent and their cultures.

I don’t pretend to produce a full catalog of the possibilities we have of learning from the past in God’s story, of learning and of changing our very selves in proper response. Call me Janus as I look to what has happened and what is now happening and only partially perceived and likely not at all understood. The past and transitions are what we can know and even the past is not well-known in a true sense until understood in light of a worldview, an understanding of God’s story in light of His purposes. In such a light, the story which is our world can be seen as unified and coherent and complete within itself. That is, it has those qualities until we learn by exploration or the world teaches us by perhaps cruel suffering something important and not yet part of the story as we understand it based upon the memories and customs found in our traditions. We explore, in some ages with faith and courage, yet even in such ages we don’t much understand those ongoing transitions which are so disruptive and more so promising. Columbus didn’t just sail the ocean blue, he blasted apart a logjam in the minds and spirits of the Europeans. The ensuing onrush of water did a lot of harm as well as still more good.

As we sail into our own oceans blue, lacking the faith and courage of Columbus, we leave the deck and settle into our cabins stocked with all the man-made items which make us feel comfortable and safe even as the boat rocks and rolls and even as we, if we are honest, admit we fear success in our journey as much as we fear failure. Perhaps more. And so those who think to be conservatives, pull out the books on the shelves of those cabins, dusting and fanning the pages to check for worms and other vermin. They gain much true wisdom and some distorted wisdom by pondering the criticisms Tacitus made of the corruptions of the Roman Empire and the highly intelligent debates between the Founders of a once promising American Republic. They stare with admiration at the paintings and statues of past centuries. Too many of them remain in those cabins, thinking them to be preserving something they label the Permanent Things.

It’s the world outside that cabin which provides the stuff and the experiences which can generate new ideas to fill new books as wonderful as those of Sophocles and Virgil and Shakespeare. But we can rise to those heights because we’ve moved on to hitherto unknown regions of God’s world. We don’t stand on their shoulders. We move some miles ahead of their graves.

We should conserve what is worth saving in light of our understanding of our past and what is happening now. We should honor, if possible, that which is no longer worth saving if it had helped to advance God’s story. We should even ponder respectfully such horrors as the French Revolution, so bloody and also so destructive of decrepit political and economic and social structures being preserved by those who were profiting from the wrong sort of conservation. Perhaps a defective moral order, one which was moreover structured to meet the needs of a prior age, could be a barrier to the development of a better order, perhaps it could be an obstruction to the forward movement of God’s story.

The story, when seen as such, is dynamic. It’s not simply some sort of game in which the pieces move themselves, sometimes with the assistance or even the insistence of God. The pieces change, even change themselves by how they move. The board changes and also shows itself to have always been different as it is explored. Many of the rules change or at least show themselves to be different as the pieces interact with each other and with the board and with the Creator. We need to move up to a higher level of abstraction so we can see what is truly permanent, invariant in terms of modern mathematics and physics. I don’t claim to have any such vision and might not reach that vision in my allotted time on Earth.

In ancient times, it was plausible to see a proper order in a crystalline form. More recently, men began to think in terms of a society which moved in a way corresponding to Newtonian dynamics. Smaller communities of men might be bound to a larger center of power and culture and that entity which was seen to reside at the center of power was unaffected by the movements of those smaller and more distant entities. Then, as was the case in Newtonian dynamics, thinkers began to adjust for the effects of smaller communities on the greater center, coming to realize `binding forces’ worked on the entire system and all the entities in that system — even the greatest and most central of entities. Over time, various thinkers have done much to account for such complications and nonlinearities. These analogies from earlier understandings of physics to moral systems or political systems didn’t live only in the human mind. They were part of the nature of created being.

And, now, we need to move on to understand a world which seems to sometimes move well outside the boundaries of any system of reason we have yet developed. As one example, I think we need some abstraction of the geometric concept of geodesic which has certainly proven its worth in physics and other sciences including the engineering sciences. In that article, we read a limited definition, but one that covers our needs and more:

[A] geodesic is a generalization of the notion of a “straight line” to “curved spaces”. In the presence of a Riemannian metric, geodesics are defined to be (locally) the shortest path between points in the space. In the presence of an affine connection, geodesics are defined to be curves whose tangent vectors remain parallel if they are transported along it.

The concept of geodesic practically invited itself into theories of gravity, which — roughly speaking — have become theories of spacetime since Einstein gave us his theories of relativity. I think some corresponding concept, abstracted properly, can play a role in restoring some serious understanding of this world and of God’s way of moving it towards His purposes. How do we get to a proper abstraction and a better understanding of our world? Let me retreat a little to talk in very general terms about the ways in which our understanding of the nature of being, including the being of moral creatures, are truly meta-physics, dependent upon ideas drawn from physics.

Plato and others did much good in the early years of philosophical and scientific thought by working with models which saw some sort of ideal forms which were static. A man, a tree, certainly a triangle, are imperfect images of some perfect entity, some Real entity. Paths, including paths of a moral creature through its life, were seen in Euclidean terms. Moral paths were usually seen as the geodesic of a Euclidean plane: a straight line. To be sure, some such as Dante intuited a more complex reality — in the opening lines of the Inferno, the path curves away from the non-observant pilgrim.

Static understandings of the world as a whole, of God’s story which is a morally purposeful narrative, are no longer possible though such understandings of classes of entities and of individual entities which are static for substantial periods of time will continue to carry much truth. We can consider first-order changes to static entities and — even more importantly — to their relationships. That brings us to an idea of an orderly but steady movement through time, corresponding to the concept of velocity in physics but leaving us in a pre-Newtonian state. Even Galileo didn’t fully appreciate the importance of second-order changes, acceleration, but that was expected since the calculus was needed for a true appreciation.

Second-order changes correspond to acceleration or to a geodesic through a curved spacetime — the curvature of spacetime might be flat and the geodesic is then a straight line. I imagine that any realistic understanding of the more general structure of our world, the structure in which we moral creatures live and move and form our relationships, will be very complex. That structure will be a manifestation of an high-level abstraction which will perhaps be a straightforward generalization of the spacetime of General Relativity and other theories of gravity. Perhaps.

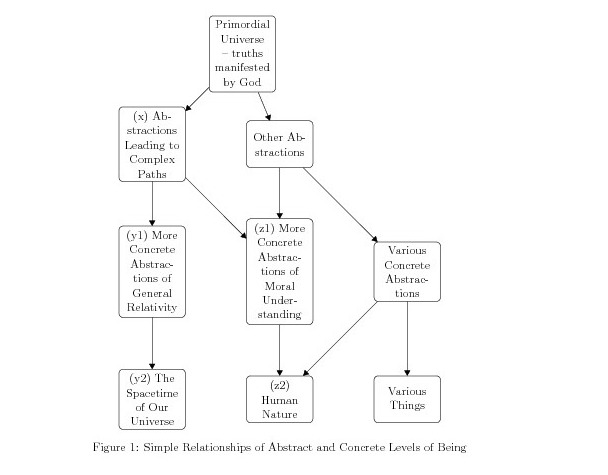

I’ll refer to the following graph I’ve used before:  .

.

We can start at Node y2, which represents our current understanding of The Spacetime of Our Universe This node is found on the bottom row. From that node, we work our way up through higher levels of abstraction until we reach a level which shows some promise for helping to understand, for example, human nature. So, by abstracting somewhat, we can reach Node x which is Abstractions Leading to Complex Paths and then travel down to Node z2 which is Human Nature including our understanding of our moral pathways through this world. This understanding is also supplemented by other abstractions as shown by the arrow from the unlabeled node titled Various Concrete Abstractions. By concrete abstractions, I intend to convey the idea of a level of abstract being which is close to that of our concrete world.

Whew!

I’ll pull things together by generalizing the old rule: just stay out of God’s way and He’ll do what needs doing. No one who’s ever said that to me has been passive. They had something in mind which kept them actively doing their duty but in a way that kept them from obstructing God’s story. So, the rule is wrong if we try to take it literally. It becomes more plausible if we try to state it in terms of a geodesic: We should become sensitive to the movements of God’s story so that we move along the main plot-line with minimum effort. We wouldn’t have to try at all to journey towards the Sun if we were in space and were captured by its gravitational field. We certainly aren’t making any effort to move along with our galaxy towards a faraway gravitation center called the Great Attractor. We also wouldn’t have to try at all to move along with God’s story if we let ourselves be captured by that story and let ourselves be pulled along toward His goals for this world.

And, yet, there are all sorts of things going on locally as we all stream, willingly or not, towards God’s purposed end for this world. As we can properly cooperate with physical forces or can defy gravity, perhaps for the thrill of some so-called extreme sport or perhaps because we like to drink and then drive recklessly along a cliff, so we can also cooperate with the forces of God’s story or can try to defy them. By responding to the more local matters in a morally responsible way, we can still find ourselves struggling against the divine narrative forces which draw us on. Sometimes, taking some sort of risk that defies the forces of God’s world, as did the early aviators, is the morally responsible thing to do. God didn’t give us a simple path to navigate and the nature of the Body of Christ as it develops is quite complex, complicated, self-conflicting in the Body’s mortal form, vulnerable to invasion and to parasitic infestations, etc.

I’ll be trying to deal with some of those complications and complexities in writings to come soon, God willing, but I’ll quickly deal with the question I raised at the beginning of this digressive essay that was, to be quite honest, hard to bring to a coherent end: Does my understanding and expansion of Quigley’s claim serve to define other forms of traditionalism and conservatism? I don’t think so, though Jews and Muslims might be able to produce a somewhat similar claim which allows for their different views on the relationship of God to His Creation. Those who don’t see this world as a Creation, or a part of a greater Creation, won’t be able to think along these lines. At least I don’t think so.

And even Jews and Muslims see God as a King who rules over a world separate from Him. We Christians see God, at least I do, as a Creator who brings moral order to the concrete realms of His Creation by the way He shapes rawer or more abstract stuff. By His very acts of manifesting truths as the raw stuff of created being and then shaping that raw stuff by various stages from the human viewpoint, and then telling a story at an appropriately concrete level, God brings about moral order. He brings it about because He is in those acts of creation and shaping since all created things are thoughts God chose to manifest in Creation. He is a Creator and a King only by analogy.

There is much to be done in understanding a world unfolding itself in human perception and — more reluctantly — in human thoughts. All of Creation, including the concrete realm which is this world, is proving to be richer and more complex than can be understood in terms of Hellenistic thought or early Christian thought or Medieval Jewish thought or any other thought which has yet taken firm shape.

My effort to understand the world in the best available terms isn’t an academic exercise. It’s part of an effort to bring a new phase of Christian civilization into being. Understanding, truly knowing, is also doing. To truly understand is be part of God’s story, moving with the Almighty and doing your own work in your little piece of the world. And in this way, I propose, a Christian truly conserves, truly saves what should be saved in tradition. He conserves by helping God to change this world and all the entities which are part of it to the goal of bringing the Body of Christ to unity and coherence and completeness.